It’s that time of year again- a glass of wine, friends and family gathered round the tellybox, staying up late with anticipation of the big day: it’s statistical Christmas- election night! All night swingometers, lots of numbers, and everyone is trying to predict who’s going to get the present they’ve always wanted, and who will get the statistical lump of coal.

I have been amazingly lucky for the last few elections, correctly predicting the EU Referendum result would be 52-48, and getting very close on the US Elections and last couple of UK General Elections. Friends have asked for my election prediction as I am viewed as some sort of Electoral Nostradamus now, so I now write down my prediction in advance and hope to be seen as the true mortal that I am by getting it vastly wrong- the statistical King Canute.

I should caveat again by saying that I am not a specialist in poling or anything like that; I maintain an interest in it, and know a little statistics of course, but am happy to be challenged, corrected, and told I’m wrong!

If you’re interested in the Maths of Elections, we recently did a podcast of Maths at: The Election ( If you’re reading this, either you like elections or you know me, both of which are great reasons to tune in)

How Polling Is Done

Essentially there’s a few ways that polling is done- by online, telephone, or face-to-face. These all come with different degrees of difficulty and expense, but generally online is the cheapest, followed by telephone, followed by face-to-face.

When polling, the idea is to interview a representative group of voters, such that the surveyed people will answer in the same way as the voters as a whole. So if 50% of people we ask vote for the Green Party, we expect 50% of the voters to do so.

There are several errors that can be made in polling such that the poll is not representative

- People refusing to answer you or worse, lying to you.

- People changing their mind between the poll and election day

- The pollsters asking the wrong people.

If you remember, for the 2015 General election, pollsters widely predicted a dead heat, but in the end the Conservatives got a lead of 7%. In a very widely circulated piece of work led by Patrick Sturgis, some detailed investigation found that, 117 pages later, essentially, the poll asked the wrong people. Getting a representative sample of the voting population is difficult.

Think of it as an exercise- if you wanted to call people up to get their views on something, how would you even get a list of people to call? Many people don’t take calls from unknown numbers. Many people don’t have time to do a telephone survey. Until relatively recently, pollsters didn’t even contact people on mobile phones, meaning that an entire younger generation without landlines were excluded. It’s fairly clear that telephone surveys will over sample older people, who are more likely to be to the right politically. Politico recently reported that only 6% of Americans respond to phone surveys (although clearly the UK may be different). Phone polling, once the gold standard, may be finished.

Similarly, online sampling may connect better with a younger demographic, and older people may be left out. Whilst it’s appealing for YouGov to pay 50p for a young person to fill in a survey on their smart wi-fi enabled potato peeler, would you really get an octagenarian doing the same? Of course there are exceptions, but how you construct the sample really matters.

Broadly, if we can get a representative sample of around 1000 people, we will be able to predict the each party to within 1.5%, and a representative sample of around 2000 people would be within 1%. So we need a surprisingly small sample to get the right number, if it is representative.

Adjusting the Polling

Pollsters know that they have sampled the wrong people by asking them demographic questions, for example. So if the voting population is 50% male and 50% female, and the sample ends up 60% male and 40% female, they weight the female responses up and the male responses down. They do this for a number of categories: age, gender, social group, education level, but also for how people voted in previous elections.

This is an entirely sensible approach to sampling, but again it relies on the respondents not lying to you in some way, and also on having accurate information about demographics of the population. Essentially, there is quite a lot of hidden judgement here about what factors are important in weighting, so whilst the polling will be random and scientific, there will be some subjectivity in the weighting. Members of the British Polling Council will publish their decisions on the weighting, but we have to take care that polls are done slightly differently and that there is some subjective massaging the numbers.

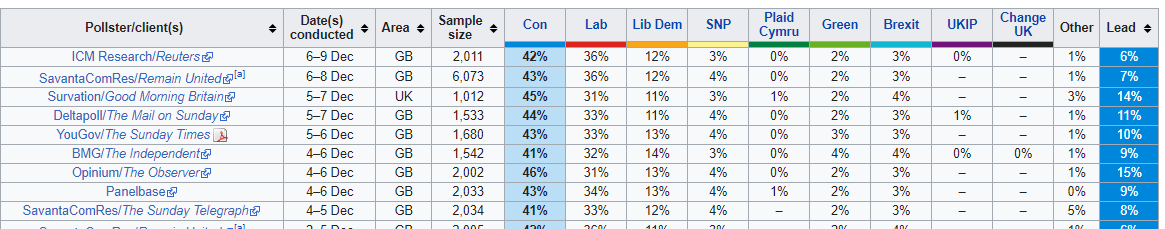

Here is (from wikipedia) the list of polls conducted in the last few days.

Look how different they are. My considered opinion is that the pollsters have not exactly covered themselves in glory for the last few elections, and I see nothing to convince me that their guesses will get any better for this one. The wide disparity between opinion polls on the same day show me how wrong they are likely to be. I therefore take these polls with a large pinch of salt.

Translating polling to a national model

Despite what people tell you, we do not have an election happening on Thursday; we have 650 elections, where everyone votes for who they want to represent them (remember this: you are not voting for Johnson or Corbyn, but for someone who will represent you!). In each constituency, whoever gets the most votes wins. The national percentage of who votes for a party is only slightly related to who gets an MP.

Here’s an extreme example of how Blue can get 60% of the votes, but still lose an election in 5 districts.

So how do we work out from sampling a small proportion of the UK electorate who wins in the UK with 650 constituencies? Essentially, we take the results we have last time. Then, if the blue party gets 1% more votes than it did last time, we add 1% to the result in each constituency. We assume that the gain in votes (the swing) is the same in every constituency across the country, and this is known as the Uniform Swing Model.

It’s rubbish. It doesn’t work. People don’t vote in the same way in Dundee as in Dungeness. There are a number of models that try to do better. My favourite is Martin Baxter’s Electoral Calculus. The model takes into account many important factors: for example, if there is an incumbent MP, that MP is more likely to do well the next time. Whilst he doesn’t list the model openly, he does tell us about the features and provide evidence that this is to be more trusted than other simpler models. Previous predictions using this model have been better than most competitors as well.

A major problem in election modelling, and even with the electoral calculus model, is that pollsters do not publish their models in full or leave them open to review. This is bad science. We can have no confidence in their correctness.

New approaches in Polling

One very clever new approach in polling is the YouGov MRP poll (Multiple Regression and Stratification). In their words:

The idea behind MRP is that we use the poll data from the preceding seven days to estimate a model that relates interview date, constituency, voter demographics, past voting behaviour, and other respondent profile variables to their current voting intentions. This model is then used to estimate the probability that a voter with specified characteristics will vote Conservative, Labour, or some other party. Using data from the UK Office of National Statistics, the British Election Study, and past election results, YouGov has estimated the number of each type of voter in each constituency. Combining the model probabilities and estimated census counts allows YouGov to produce estimates of the number of voters in each constituency intending to vote for a party. In 2017, when we applied this strategy to the UK general election, we correctly predicted 93% of individual seats as well as the overall hung parliament result.

This is certainly, in my opinion, the way forward in polling- we’re borrowing knowledge from across the country, so we know that unemployed 45 year olds with a degree in Norwich are likely to vote in a similar way to unemployed 45 year olds with a degree in Cromer. Overall, the huge sample size as well helps smooth out some bumps, but this alone doesn’t help with accuracy too much, as even a small sample can be accurate if representative.

Does it work? In my opinion (and this is controversial), no! At least, it’s not been tested. The YouGov model has only been tried in anger at the 2017 election, and it correctly predicted 93% of individual seat results. However, is that a great achievement- 579 seats did not change hands at the last election, meaning you can get an 89% prediction accuracy just by predicting the status quo. The YouGov model got it wrong at the detail level as well. To be fair to them, they have only just started with the model, and have limited data points (one) available. But although they are not definitely using a better method, the problems with polling the right people, and the fact that demographic information on each constituency is not 100% accurate, are not resolved. Also, they have not (to my knowledge) submitted their model to peer review, so how can we say it is justified?

In particular, a big problem in polling (that isn’t lost with the YouGov method) is working out the likelihood of people to actually get to the ballot box. For the traditional polling, they ask people how likely they are to vote, and discount those that rank themselves less likely. For the Yougov model, the turnout is predicted by the model itself: they use the last election to predict this, so a 25 year old in 2017 will have the same likelihood of voting as one in 2019. Turnout is likely to be a big factor, and with a close election, one seen as important politically, is this assumption really valid? My belief is that this will be the Achilles heel of the YouGov model as turnout does vary significantly. With a December election, and a very strange electoral climate in the UK, we could see substantial differences.

Turnout over previous elections:

(Image from https://inews.co.uk/news/politics/turnout-general-election-uk-voter-brexit-referendum-europe-elections-1337817 )

Putting it together and making a prediction

Some more comments before I nail my party political colours to a mast!

- Momentum. The polls are certainly narrowing. There is no way that a pollster can take into account momentum as people can change their mind in the last days of the election- this is the point of campaigning! Whilst the pollsters show the Conservative vote fairly steady, there is some evidence that Labour are gathering some votes, mostly at the expense of the LibDems. Note that whilst I don’t trust the individual polls, as long as the polls are repeated in the same way, we can get some evidence that things are moving in or out of one parties favour.

- Turnout- crucial as always. The YouGov MRP is the best poll, but I think has perhaps modelled turnout wrong. I think the turnout may well be higher (those that have registered for a December election are more likely to vote), so again I think this will not favour the conservatives. (The weather forecast is for lots of rain- this anecdotally favours the Conservatives, but not sure there is evidence of this. There is a lot of guff about turnout, and we really get a datapoint once every 4 or give years, so who knows?)

- Don’t knows- most polls exclude don’t knows. I think there is no reason to guess that don’t knows will vote one way or another. We have no evidence either way, and I see no clear pattern in the polls I have looked at. My guess is more “Don’t Know’s” might be torn between remain parties, but difficult to know.

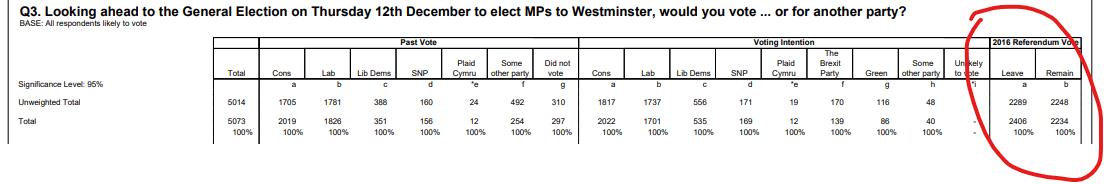

- Demographics. Looking at the polls (and this applies both to online and phone polls), we can get a great deal of detail about how people said they voted in the past compared with how they will vote in the future. So for example, this survey by comres surveyed 5014 people, of which 2289 said they voted Leave, and 2248 voted Remain.

They have then weighted the leave voters up to the referendum result (52-48). I think this is wrong- at the very least, demographics mean that many of the older electorate have frankly died in the 3.5 years since the referendum, and I do not think the polling companies are weighting correctly. This pattern is similar in other polls I have checked I find it suspicious that both telephone and online polls have weighted in favour of the conservatives, and I think there could be some overweighting here- about 1-2% against the Conservatives.

I also think that demographic change may be a large factor. The last UK Census took place in 2011- and I wonder how much these projections have been updated in the 8 years since. The effect of this is more difficult to see.

Prediction

I therefore make my GB prediction as follows:

Conservative 41%

Labour 35%

Lib Dem 12%.

With some tactical voting, I predict that the GB seat counts will be

Con 319 Lab 251 LD 15 Nat 45 Green 1 Speaker 1

(NI has 18 seats, not listed)

This would be right on the cusp of a hung parliament.

Good luck everyone, and don’t forget to vote!